This is a follow on to our previous guide exploring ways in which audio recording may help with parliamentary work, and explaining how to do it on a modest budget.

I don’t consider myself a video professional, but I’ve made a several budget educational videos, and recorded meetings and conferences. I participated in two working groups of the British Computer Society, looking at how BCS branches and groups might video meetings, primarily for the benefit of those who can’t attend events in person.

So, you might expect me to be an enthusiast for video technology. In fact, I often urge caution, because making good video takes more skill and time and planning than audio. Good video kit is expensive, and often difficult to transport. Storing digital video can consume huge amounts of memory, and costs bandwidth to transmit; with both image and sound to kick into shape, the editing process is more complicated; and video technology and technical standards have been changing very fast. It’s been hard to keep up.

If video from an event will be no more than a speaker’s ‘talking head’ and some Powerpoint slides, I tend to suggest concentrating on a good quality audio recording. It’s cheaper, easier, and in the edit it’s so easy to improve a presentation by snipping out the ‘Ums’ and ‘Ers’… and you can’t do that as seamlessly in a video edit.

However, it’s not my job to put you off! Visual content can be very informative. I’ve filmed at graphic design conferences, where slides and other images were an essential to understanding the subject, and audio-only would be quite mystifying.

Anecdotally, video is said to appeal better to a younger audience than audio alone. It used to be said that quality expectations of video production have been driven high by television and movies, something we’s be hard put to match; but in the era of YouTube and Facebook amateur video, maybe that is less true?

A technical revolution: video everywhere

Sensor chips for image capture came to consumer digital cameras and camcorders about 25 years ago. Since then, they have been attaining higher resolutions, better sensitivity to lower light levels, and have become cheap. What was once an exotic technology found only in space satellites is now in everybody’s smartphone! This revolution is boosted by ever more powerful video-signal processing chips, and the capacity and speed of solid-state memory, such as the near-ubiquitous SD memory card.

In preparation for this article, I compiled a list of devices that now ‘do video’. Within minutes, I had listed well over a dozen. There are smartphones and tablets; bodycams worn by police, cyclists and daredevil skateboarders; dashcams and baby monitors; cameras for home security or watching wildlife; cameras on drones. There are digital stills cameras, from amateur to professional grade, which now also function as video cameras; and at the high end, specialist video cameras with which you could even shoot a feature film.

Ask: why are you doing this?

As in my audio-recording article, let’s start by examining possible purposesfor making video. I divide these into three rough categories:

‘Evidencing’ – when the main point is to have a visual record. Dashcams, bodycams and security cameras are designed expressly for this purpose, but there are many examples of people pulling out a smartphone to bear witness – from a mate’s skateboarding prowess or a spat between cat and dog, to a terrorist or criminal attack. Look at how much smartphone footage makes it onto the TV news (and Facebook) these days!

‘Presencing’ – Here, I mean when you bring someone’s eyes to watch something beyond their immediate view (usually in real time, without making a permanent recording). An example is using webcams for a teleconference or Skype chat; another is streaming live video from a public meeting to reach a wider audience. Eliza, a friend in Ghana, runs a restaurant and music spot. Every Friday (reggae night) she puts an iPhone on a tripod stand, points it at the bandstand and part of the dance floor, and streams live video to Facebook. It’s making her establishment famous, at low cost. ‘I have next to no PR budget,’ she says. ‘Social media exposure is worth those 4G data fees!’

‘Presentation’ – By this I mean when you want the final product to look really The purpose of the video may be to explain, persuade, demonstrate or make a case in a convincing and professional manner. The filming should be well-lit, the camera handled smoothly, the audio capture crisp – and the format in which it is recorded should make it easy to edit afterwards, cutting together scenes and making use of graphics and text overlays. Maybe you can aspire to this quality of production yourself, with access to suitable equipment and software; or you may decide it’s more sensible to bring in professional outside help (paid or volunteer).

A few simple, low-cost solutions

Smartphone videography. I’ve already mentioned the smartphone as a video camera, and it has the unique advantage of Internet connectivity – as used in Eliza’s video-streaming escapades. But your smartphone can make better video with a couple of modest additions:

A smartphone tripod. Tripods for smartphones are not designed for dynamic panning shots – they are too flimsy – but they will hold a phone steady, and are easy to carry and set up. For example, the Paladinz Phone Tripod (£15) weighs just 360g and expands to a height of a metre. It even comes with a Bluetooth pause-record controller for the phone.

A compatible external microphone. For smartphones, the commonest type is the sort you clip on a subjects’s clothing, with a thin lead connected to the phone. Many cost less than £20. They are useful for interviews or ‘video selfies’, but they won’t help you get good audio at a meeting, or from a speaker on a platform. Try a directional mic: a well-reputed one for phones is the Røde VideoMic Me at about £60. Like a small torch in appearance, it is clamped to one side of the smartphone. (http://www.rode.com/microphones/videomicme)

Super webcam. Here I’m using ‘webcam’ to mean a camera attached to a PC or laptop, as used with Skype and video conferencing applications. Many laptops have a webcam built in, but an external, USB-connected webcam is easier to point where you choose, and usually works better in dimmer light. For under £100 you can get webcams that work at high resolutions such as 1080p or HD, and have stereo mics built in. An example is the Logitech C920 HD Pro, at £70.

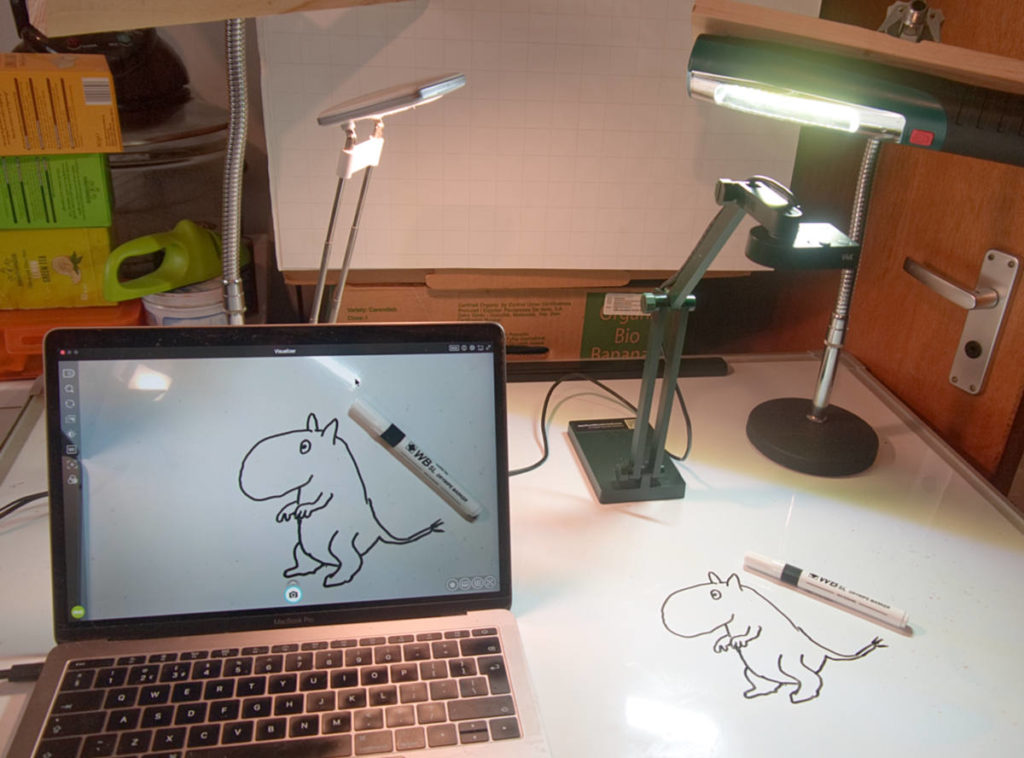

I accidentally took a step in this direction when I bought an IPEVO V4K camera for £99. This works like an overhead projector: you point it down at a document to project the image onto a screen. It turns out that it also does ‘super webcam’ stuff, with an 8k imaging chip, and I’ve been testing it for medium-quality video streaming too.

To use a webcam and record the video for later editing, you’ll need software that captures video and audio from devices attached to your computer, and saves the combination to your hard disk. I did this recently, recording the whole of a two-day training workshop. I linked an old camcorder to my laptop with a FireWire cable, and my audio mixer desk via USB, and captured the mix with QuickTime Pro 7 software for Mac. The accumulated raw ‘product’ came to about 70 GB, but… I had plenty of space on the hard disk.

This IPEVO camera is based on high-definition webcam technology. Its primary function, when the computer is attached to a data projector, is to show documents and other objects live to an audience, but it can also take still images and record video to disk, through various software packages. Other ‘super-webcams’ are available from different makers, with Logitech a prominent brand.

The ‘fancy camera’ route. Here I mean serious digital stills cameras which also record digital video. Canon and Nikon have been leading rivals in this market, bringing video capabilities to their digital single-lens reflex cameras (DSLRs). A major advantage of these cameras is that you can change lenses to customise for different situations, such as extreme telephoto or wide-angle coverage. (When filming meetings, I prefer to do so from the back of the room, for which you need some telephoto capability.)

The Sony Alpha 6000 is an example of a mirrorless DSLR, small enough to be carried in a jacket pocket, but delivering excellent still image quality from low light levels, for less than £500 with the short zoom lens shown here (other lenses available). In addition, it has fairly respectable functionality as a video camera, saving either AVCHD or MPEG-4 movies files at a variety of resolutions. It could certainly handle an interview, but a file-size limit of 2 GB means it can’t record continuously for more than about 20 minutes.

If you’re not happy with the quality of audio picked up by the tiny embedded microphones, the smart hot-shoe can mount a dedicated stereo microphone with two swivelling heads.

Note that in this picture, the camera is supported by a stout tripod with a ‘fluid-effect’ video head, for smooth panning to track a mobile subject.

DSLR videography seems particularly popular in the music video world, where clips and shots tend to be very short. A couple of years ago, a music promoter friend bought a second-hand EOS 5D Mark II: Canon’s first digital SLR camera to support full HD recording (1920 x 1080 pixels). He’s hoping to make his own music videos. Certainly the image quality is superb – one would hope so from a camera costing a few thousand pounds with lenses! After spending that tidy sum, he turned to me for help in buying a stable professional video tripod, extra batteries, battery chargers and memory cards.

Memory card capacity can be an issue with these cameras. If you shoot high-resolution, minimally compressed digital video (best for editing and professional production), you will see memory gobbled up at amazing speed: when filming with 4K resolution, 4 GB will be gone in just under 40 seconds! You should seriously ask yourself whether you can’t serve your purposes by filming at a lower resolution.

When standards for SD and Compact Flash memory cards were first devised, they adhered to a media formatting standard called FAT32, which doesn’t allow digital files bigger than 4 GB. Recording a full public lecture will need serious amounts of memory for storage. Some cameras will truncate your recording; in the better ones, the recording gets sliced into sequential 4GB chunks, and you have to glue them together again in editing. The very fanciest cameras now use advanced memory cards with formats such as CFast, which can store enormous files.

Mirrorless Micro Four Thirds. Other kinds of digital stills camera have dipped their toes into digital video-taking, such as the new ‘mirrorless Micro Four Thirds’ (MFT) machines. They are like DSLRs, but built around a smaller albeit high-resolution imaging chip, and they dispense with the pentaprism viewfinder and mirror of the classic SLR camera in favour of a purely electronic viewfinder. These design decisions have made them quite affordable.

Some years ago with regret and resignation I decided that video technology was changing so fast that I could no longer afford to keep up wityh the latest gear – plus, I’m getting a bit old for dragging tripods and video cameras around. But now I am thinking, a small MFT camera would let me carry a compact stills camera in my pocket, with reasonable-quality video recording capability too. The Sony Alpha 6000 camera is on my wish list (£500 with a standard zoom lens).

Professional video cameras. In the interests of completeness I should mention these, though I suspect none of my readers would spend £5,000 on a video camera body (without any lenses, mind you.) However, in a photo caption below I briefly describe one such camera from Blackmagic Design, so you can understand why these machines help the pros to do their job more reliably. And if you do hire a pro, they might bring one with them!

Professional video cameras are used in television studios, outside broadcast and these days even for making feature films. The URSA range of cameras from Blackmagic Design are representative of this class, with prices (for the body alone) between £3,000 and £6,000. This Blackmagic URSA Mini Pro 4.6k G2 is currently top of the range. Note the many surface-mounted controls and lens focus and zoom rings which give the operator instant access to the camera’s features.

With its large sensor array generating feature-film quality footage at up to 300 frames a second, 4608 x 2592 pixels, this camera generates huge amounts of data, and takes two CFast memory cards, and can even plug into a USB-C external hard disk for extended shooting. To handle difficult lighting conditions, a special 15-stop High Dynamic Range file format can be selected, rather like the RAW format on the better digital stills cameras, so the studio can afterwards grade, process and edit the footage to best effect in DaVinci Resolve Studio software.

Photo: Blackmagic promotional material.

Sound investments

I cannot over-emphasise how important good sound capture is to video production, especially in the political sphere where the spoken word is our currency. Even pricey DSLRs have ridiculously inadequate onboard microphones, but at least they have audio inputports. You can mount a broadcast quality directional mic to the flash-mounting shoe, such as the Røde VideoMic with its integral shockmount (mono), or the Sennheiser MKE 440 (stereo). There are also adapters such as those from Beachtek (discussed later) which let you tap into just about any sound source.

Then there is camera support. I’ve already mentioned video tripods, which come at a range of price points. If you are wanting to actively manage the ‘pan’ and ‘tilt’ of the camera, for example to swing the camera between speakers, you’ll want a robust and heavy tripod with a ‘fluid effect’ video head and a steering handle. These dampen camera movements, making them less jerky.

Tripods can tie you to one spot, but a ‘spider dolly’ is a device that sits under a tripod and gives it wheels so it can be moved across a smooth floor to a new location. ‘Steadicam’-style devices let you walk freely with the camera while smoothing its movements. One very useful yet under-rated accessory is the monopod, with some of the stability of a tripod, but far more portable and easy to reposition, and usable in a small space.

Many digital cameras and camcorders now have ‘optical stabilisation’. Movement sensors inside the lens detect any shaking, and the mechanism moves prisms around in the light-path to steady the shot. If your camera has got this feature, turn it on.

Lighting, and other environmental matters

Light within the filming environment can make a tremendous difference, including in ways you might not expect. Adequate and even lighting, without strong highlights or shadows, is easiest to cope with, especially for lower-cost video cameras and devices which cannot cope with ‘high dynamic range’ situations.

But we don’t always have much choice. Suppose you’re filming a speaker on a stage, picked out with a spotlight. Automatic exposure may sense the overall darkness of the scene, think the lighting is inadequate, increase the lens aperture or alter the ‘gain’ on the sensor, and as a result the exposure burns out the features of the speaker’s face. An experienced videographer with better equipment should be able to override this auto-exposure to compensate.

Low light levels also make focusing more difficult. Autofocus mechanisms rely on having enough light to do ‘feature detection’. Cameras which manage exposure by adjusting the width of the aperture gateway in the lens (e.g. DSLRs) can compensate for low light levels by opening the aperture wider: but this results in shallow ‘depth of field’ – that means, it reduces the extent to which things are in focus in front of and behindthe actual focus point, and the subject is more likely to fall out of focus. These auto-gremlins can be kept under control if your machine lets you switch focus control to manual.

When making close-up video indoors, a portable light mounted on or near the camera can help. White-light LED arrays are popular for this purpose these days, because they provide a decent amount of light without quickly draining their battery. (I have a cheapskate version of this – a couple of rechargeable LED car inspection lights from Lidl, of all places!)

On a sunny day outside, contrast between highlights and shadows e.g. across a person’s face can make satisfactory exposure difficult. Fill-in lighting to soften the shadows will help, and could be provided simply by someone holding up a white-painted sheet of hardboard as a reflector.

Sound. If ambient noise interferes with recording, solutions include getting a mic as close as possible to the speaker, like a news reporter on location; the mic could be linked by cable, or by radio. If you can’t get a mic to the speaker, a highly directional mic helps by rejecting off-axis noises.

Beachtek (https://beachtek.com/) makes audio adapters for camcorders and DSLRs. With these and similar, you can feed in audio from almost any microphone or sound mixer, and volume control knobs give the camera operator the power to adjust the audio level. When I filmed the Information Design Association conference some years ago, we had several microphones feeding into my mixer desk, operated by a student volunteer. The combined audio was fed from the desk through 30 metres of shielded XLR cabling, to my camcorder at the very back of the hall, with a Beachtek unit between it and the tripod.

Video editing and conversion for distribution

When I started making video in the early 1990s, editing was a cumbersome process using three videotape recorders and a video switcher, and the product was assembled step by step – a ‘linear A/B roll edit’. Nowadays we dump all the digital source material – video clips, audio clips, graphics – onto the hard drive of a standard computer, and assemble the bits along a Timeline using a video edit application. If changes to the edit are required, you don’t have to start again from scratch – just move stuff around on the timeline.

As for video editing software, I’ve mostly used Apple’s Final Cut Pro, and Adobe Premiere. They are rather expensive, and with my current constrained budget I am moving to NCH VideoPad. Camtasia is another popular editor. A friend who owns a serious DJI Mavic 2 video drone makes lovely compilations of her coastal flights, to background music, and so far is doing a nice job with iMovie software for Mac (it’s free!).

Video editing is too complicated a process for me to deal with in this article, but let me leave you with a few points:

- All video source clips should be the same resolution: plan ahead for that. You might however export finished work at a lower resolution.

- The software will enable all kinds of ‘transitions’ between clips, many quite wacky and distracting. But unless you are shooting a music video, I suggest straight cuts and crossfades.

- Avoid ‘jump cuts’! This is when you slice a bit of time from the middle of a scene (maybe a speaker made an off-colour joke and you want to lose it). But the result will be a jerk (in this case, I don’t mean the speaker). You can cover the gap by making a ‘L-shaped cut’ (where audio from the first clip touches the audio from the second, but the video component is ‘peeled back’ on either side), then drop in video from a cutaway shot – perhaps a view of the audience. With planning, you don’t need a second camera to do this, just remember to collect a few neutral-looking cutaway shots in case you need them later.

- Odd as it may seem, you can use video editing software to make a show with no video clips at all! I have made several ‘fade-dissolve slide shows’ with narrative, for educational purposes.

- You can layer several video layers (e.g. subtitles over video) and several audio layers too (e.g. fade down actual speech of the subject and fade up an English translation).

- At the end of the process, there are various formats to which you can convert for distribution. For use on the Internet, the usual choice is some flavour of MPEG-4 (.mp4), compressed to work satisfactorily even where the viewer’s bandwidth isn’t that great. Again please excuse me, but it’s a matter too complex in detail for this overview article.

Video planning and editing

Any video production with ambitions to some quality should be planned. A promotional video is to a large extent a staged production, and can benefit from a script, even a rough storyboard to plan shots and angles. In other situations, such as events or interviews, you have to work with anything that happens in front of the camera, but you might also write and record a narrative voiceover, and create graphics to cut away to – depending on the subject, this could include graphs and charts, bullet points that build on screen, or data maps.

It used to be easy deciding on a video format, when choice was dictated by the long-standing norms for terrestrial television (in Britain, the PAL format, 720 x 576 pixels, 25 frames a second and interlaced). These days we have at least four more different digital camera formats in fairly common use (720p, 1024p, HD and 4K). What’s more, these can be captured with different degrees of data compression – some of which will entangle the data from adjacent video frames and make satisfactory editing difficult. As for how video is to be delivered, the television screen no longer sets the rules, and Internet delivery – now the norm – supports just about any resolution, frame rate or even orientation (horizontal or vertical).

These planning decisions will affect things like what video equipment you use, what extra skills need to be roped in, how you will produce overlay graphics, and what your budget will be. If you feel you may be floundering in some of the technicalities, one remedy might be…

Seeking professional help

I hope this overview of the range of genre and technology choices helps you to think through what video can do for you – and, what you personally can do to make video yourself. If you don’t feel emboldened enough to ‘DIY’, you might engage outside help.

A professional videographer brings three sorts of assets. Firstly, they have knowledge and skills and experience; they can foresee where problems may arise, and how to to plan a way around them. Secondly, they will have their own videography kit, access to an editing workstation, and probably they have accounts with companies who rent out any specialist items required. Thirdly, many videography projects involve assembling a small team, and your professional will have the contacts to recruit an interviewer, voiceover talent, sound specialist or whoever else is needed.

How do you find a suitable video professional? As with other media production contractors such as graphic designers or website designers, the more established ones will have web sites with showreels of previous work, though this won’t tell you what they are like to work with as people – how diligent at meeting deadlines, for example! Students of film-making may be able to help within a team, though they may need direction from a more experienced practitioner – something which the student may well appreciate.

Appendix: some features of a professional video camera

One of the most visible features of any video camera oriented towards the professional video worker – whatever the age of the technology – has long been that the body of the machine is covered with myriad knobs, switches, other control surfaces, and meters. To some people that might make the machine offputtingly scary, but it’s appreciated by people who like fast feedback and control – we want the capability at our fingertips to make instant adjustments, rather than having to burrow through nested arrays of stupid menu screens. In particular, we want rings and knobs that give us manual focus, manual zoom control, and adjustments to exposure and audio recording volume. We also want to plug in monitoring headphones, and audio sources, and when working on a tripod, many people like to use a flip-out LCD monitor – maybe adding a larger one than that which is built in.

As an example of a high-class video camera, consider the Blackmagic URSA Mini Pro 4.6K G2. I’m not expecting any of our readers to rush out at buy one of these at over £5,000 for the camera body alone, but I’m highlighting some of the leading technical features so you can understand what professional users look to such cameras to do for them:

- The image sensor chip is about the size of a 35mm film frame. It has a high resolution suitable for documentary and feature film-making, and fifteen stops of dynamic range (HDR) to render both highlight and shadow details better in the same shot.

- The sensitivity in low light levels is pretty good, and for when the light is excessive, there are dial-in neutral density (ND) filters – like a set of internal sunglasses for the chip.

- You can choose to fit to the camera body a wide range of lenses to suit your job and budget; and choose between a comfortable high-resolution eye-level viewfinder or a seven-inch studio viewfinder. Other bolt-ons can turn the camera into a tripod-dweller or a shoulder-mounted walkabout machine.

- Just like some better stills cameras can be set to shoot ‘RAW’ image files that have more light levels stored in them (and which you afterwards process), this G2 offers ‘Blackmagic RAW’ format, and software to ‘develop’ the data afterwards.

- To cope with the huge data storage requirements of high-resolution digital video, this camera takes two high-capacity CFast recorder cards at the same time, or you can plug in a USB-C external hard disk. This latter option makes it easy to plug the camera footage straight into to the editing computer.

- The interfaces available on the camera include SDI (serial digital interface). These could be used by a team running several cameras to cover an event live, where a director sits at a video mixer/switcher panel and chooses which camera’s point of view to use at each stage of the activity.

Conrad Taylor is an independent writer, teacher and media worker.