We’ve all been there. 800 tightly-written words about that proposed industrial estate, and what it does/doesn’t bring to the constituency. Sparkling prose, crisply edited. But sitting there on the blog it needs…something to lift it. A picture!

As I say, we’ve all been there. A couple of seconds later Google has found dozens of photos. We do that clever screen-snipping thing; don’t even bother to save it. Click→paste and it’s up. Job done.

Then a few weeks later, other words arrive, in a letter to the office. But they’re firm, direct ones. This is our image! You are in breach of copyright! You must pay us £1500 (or £750 within next 14 days), and so on.

You have been busted.

It’s easily done; that lovely aerial picture was tracked down using automated image matching software. The rights holder got an alert, checked it was used without a licence, and triggered the collection process. Letters like this go out every day, and they are very imposing documents, designed to strike fear and get a result.

Will the pursuers keep pursuing? There’s plenty of track record that says they will. Your first instinct will be to remove the offending image. Not going to help. There’ll be screenshots, not just of the usage, but of the page’s source code that shows you’ve uploaded it to your web host, irrefutably ‘creating a copy’. There’ll be evidence of what and when and where, recorded well before that letter of claim went out, and it will stand up in court.

And this is just if you’ve used something owned by one of the big image libraries. Pick something more topical, and you may well have the photographer coming after you directly. (I took the photos of the last prime minister in the close company of a certain US tech entrepreneur, and I had a very busy couple of weeks when the story broke.) We base our offer of settlement on the demonstrable market value of an image, and that can be eye-wateringly high.

Funny things, photos. We hold them so dear at times, yet invariably wince at the thought of paying even pennies for them. We recognise their value – why else would we be wanting to use them? – yet often struggle to think of that as an actual monetary value. Perhaps you feel that pictures on the internet are fair game. (In honesty, almost everybody does, at some level – except us photographers, of course).

I can’t fix this. It’s been deep in our collective moral make-up since technology gave us the necessary tools. If I can’t persuade you to reframe that “valued but not valuable” paradox, then at least I can help you avoid getting pursued.

So what are you to do? Firstly and obviously, don’t search out photos to use without thought. If you’re not sure of the rights position, don’t risk it. You can, of course, spend a few quid (typically £5-£50 for a small image for non-commercial use) at one of the big image libraries. They have lots of choices, and you’ll probably find something highly relevant.

But you might not want to spend even that. So what are your options?

Bear in mind that almost every image created in the last 70 years will be under some sort of copyright. “Public domain” collections (where copyright has been renounced entirely) do exist: the Wellcome Collection, British Library and others have put considerable effort into releasing these.

There are also collections of photos whose owners, for whatever reason, have chosen to release them free of any requirement to pay or even give credit. They can be very generic images, and often very heavily used across the internet. Your piece could look a lot like many others. I think you can do better than this.

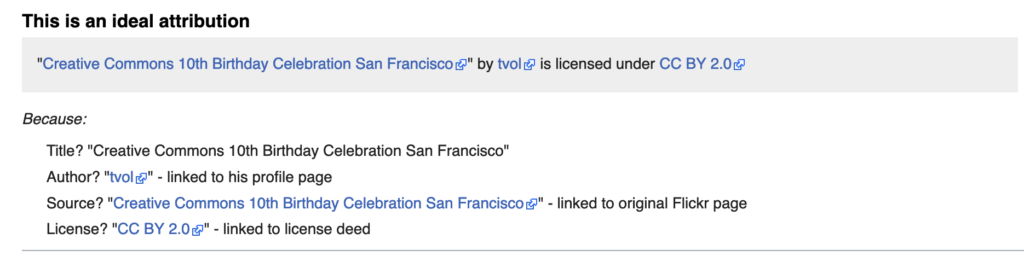

More usefully, although they remain under copyright, some image owners assign an “open licence” to their pictures – examples include “Creative Commons” and “Open Government” licensing. You can use the picture for free, provided you adhere to some conditions. I won’t get into all the licensing flavours here, but you’ll almost always be required to ‘attribute’ the image with a line of appropriate text below your post.

The image-hosting platform Flickr is a great place to find these. You can search not only by image description, but also by type of licence. But still be wary, especially if the picture features recognisable people. There’s a lot of nonsense written about (imaginary) image rights, and rights to privacy, and I won’t add to it here. But suffice to say that although you’re unlikely to be in trouble with the law or the lawyers for using someone’s face, there’s a non-zero chance that they might still object, and create a fuss that you probably don’t want to spend your time dealing with. Avoid faces, especially of the general public.

One of the best-known collections of political faces is of course the official parliamentary portraiture collection, by Chris McAndrew, released under open licence. Not only can you use them for free, the licensing also lets you alter them. In case you ever wanted to see “the PR edit” of some of your favourite parliamentarians.

Wikipedia’s also a great source. The images that power its articles are stored in the “Wikimedia Commons”: this includes everything that’s been submitted for Wikipedia use, even if not currently being used in an article, and it’s an entry requirement for this collection that the owner assigns an open licence to it.

But do remember that attribution. I am the rights holder for this image of Sir Tim Berners-Lee. It’s very popular with news organisations. When times are hard (and they’ve been very hard) I’ve gone round with the collecting tin for organisations who didn’t bother to attribute. I showed some leniency to a collective of well-meaning web nerds who were using it, but drew the line at obviously commercial sites.

And if I found something on a post related to politics or politicians? Well, they’re all fair game, aren’t they?

EDITOR’S NOTE: If your office receives a ‘copyright infringement notice’, please inform Tara Cullen in the Members’ Services Team immediately, and do not respond to the notice until you have discussed it with her.